"This whole Chapter of Bernier deserves every Man’s Reading" — Trenchard & Gordon

AM | @HDI1780

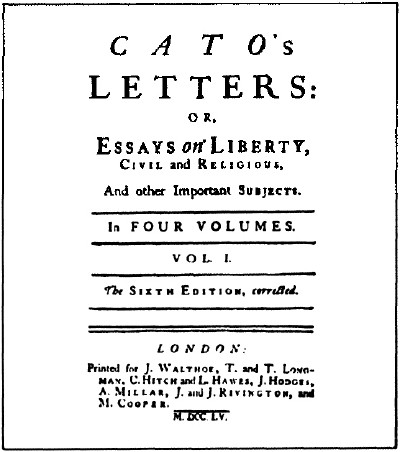

As I have stated many times in the blog, and as I try to explain in the book, the 'institutional theory' of credit markets is the cornerstone of Guillaume-Thomas Raynal's political economy. The idea is simple: without a rule of law, property rights are unstable and the supply of credit contracts, thus leading to high interest rates and to low volumes of trade (and to very little innovation). But what are its origins? Prior to my 'discovery' of François Bernier, I had always thought that John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, the authors of Cato's Letters, had pioneered the link between governance and credit that Montesquieu and others subsequently took up.

But I changed my mind last week. By pure coincidence, I came across the article "Liberté politique" in volume 23 of M. Robinet's Dictionnaire universel des sciences morale, économique, politique et diplomatique; ou Bibliothèque de l'homme-d'état et du citoyen, 1782 (pp. 208-226). It contains the very interesting Réfléxions d'un Anglois sur la nature, l'étendue & les avantages de la Liberté civile, a translation of Cato's Letter No. 67, published on February 24, 1721. It turns out that Trenchard and Gordon derive their ideas from ... François Bernier! (*)

* * *

Obviously, I hadn't noticed that when I first read No. 67. In Vol. II of the 1723 edition of Cato's Letters, the Frenchman is introduced as "the great and judicious traveller Monsieur Tavernier" (p. 143). The mistake is corrected in subsequent editions. To their credit, Gordon and Trenchard provide a "summary Account" of the last chapter of the History of the Great Mogul (the "Lettre à Monseigneur Colbert", which I plan to publish in the blog). I am beginning to suspect that Histoire des deux Indes owes much to Trenchard and Gordon and their fine reworking of Bernier. Here are the relevant passages:

There People will dare to own their being rich; there will be most People bred up to Trade, and Trade and traders will be most respected; and there the Interest of Money will be lower, and the Security of possessing it greater, than it ever can be in Tyrannical Governments, where Life and Property and all Things must depend upon the Humour of a Prince, the Caprice of a Minister, or the Demand of a Harlot. Under those Governments few People can have Money, and they that have must lock it up, or bury it to keep it; and dare not engage in large Designs, when the Advantages may be reaped by their rapacious Governors, or given up by them in a senseless and wicked Treaty: Besides, such Governors condemn Trade and Artificers; and only Men of the Sword, who have an Interest incompatible with Trade, are encouraged by them.

For these Reasons, Trade cannot be carried on so cheap as in free Countries; and whoever supplies the Commodity cheapest, will command the Market. In free Countries, Men bring out their Money for their Use, Pleasure, and Profit, and think of all Ways to employ it for their Interest and Advantage. New Projects are every day invented, new Trades searched after, new Manufactures set up; and when Tradesmen have nothing to fear but from those whom they trust, Credit will run high, and they will venture in Trade for many times as much as they are worth: But in arbitrary Countries, Men in Trade are every moment liable to be undone, without the Guilt of Sea or Wind, without the folly or treachery of their Correspondents, or their own want of Care or Industry [...].

Here's the French version. Note the term grandes entreprises, often used by Raynal and Diderot (HDI 1780, x.10; xiii.8; xvii.8; xvii.30):

C'est là que les habitans oseront se vanter de leurs richesses ; c'est là qu'on formera la jeunesse au commerce ; & que le négoce & les négocians seront en honneur ; c'est là que les intérêts de l'argent seront plus bas, parce que chaque particulier jouira d'une plus grande sureté dans ses possessions ; au-lieu que dans les Etats tyranniques, la vie, la propriété des sujets, toutes choses, en un mot, dépendent de l'humeur d'un prince, du caprice d'un ministre ou de la demande d'une courtisane. Sous ces gouvernemens, il est rare que le peuple ait de l'argent, & ceux qui en ont ne le perdent jamais de vue, ou l'ensevelissent afin de le mieux garder ; on ne forme pas de grandes entreprises, sur-tout quand on se doute que les avantages qu'on en retireroit pourroit exciter la rapacité des gouverneurs ; ou que l'on prévoit qu'ils n'auroient nul égard à la sainteté des traités. Il n'est que trop ordinaire d'ailleurs, que les gouverneurs ayent du mépris pour les commerçans & les artistes.

On ne considère que les hommes d'épée, dont l'intérêt est incompatible avec le commerce. C'est pour ces raisons que les négocians ne s'appliquent point à leur métier avec autant de satisfaction que dans les pays libres. Dans les pays libres, on dépense son argent pour son usage, son plaisir ou son profit. On cherche tous les moyens de l'employer utilement & à son avantage. On invente chaque jour de nouveaux projets ; on imagine de nouvelles branches de commerce ; on établit de nouvelles manufactures. Quand les commerçans n'ont rien à craindre, si ce n'est de la part de ceux à qui ils confient leurs marchandises, le crédit ne peut manquer d'aller haut ; & chacun tâchera de se maintenir dans le commerce aussi long-temps qu'il le pourra. Mais dans un gouvernement arbitraire, le commerce est sujet à des révolutions bien plus dangereuses que la mer & les tempêtes. Sans rien craindre de leur correspondans, les négocians ne seront jamais certains de recueillir le fruit de leurs veilles & de leurs soins, ni l'artisan celui de son industrie.

(*) John Dryden's Restoration drama Aureng-zebe (1675) did much to promote Bernier's popularity in England.

________________

No comments:

Post a Comment